It’s no wonder Emmanuel Boss is smiling, he is only working when the sun is shining. Yes, it’s absolutely true, and there’s a perfectly logical explanation for it.

– It’s a sunny day algorithm because of the satellites, says Emmanuel Boss, Professor at the School of Marine Sciences at the University of Maine, USA.

He is working on one of the most challenging and promising frontiers of oceanography, connecting satellite observations of the ocean’s color with real, biological samples from the sea surface.

– We want to use this data to develop algorithms to observe biodiversity from space. And the only way you can do it is when the satellite sees the ocean.

Ocean colour

Instruments such as OLCI on board ESA’s Sentinel-3 satellite, NASA's MODIS on board Aqua, VIIRS on board JPSS, and the PACE satellite, all monitor the ocean’s colour, an indicator of what is happening in the uppermost layers of the sea. But these observations need to be interpreted to reveal the whole story.

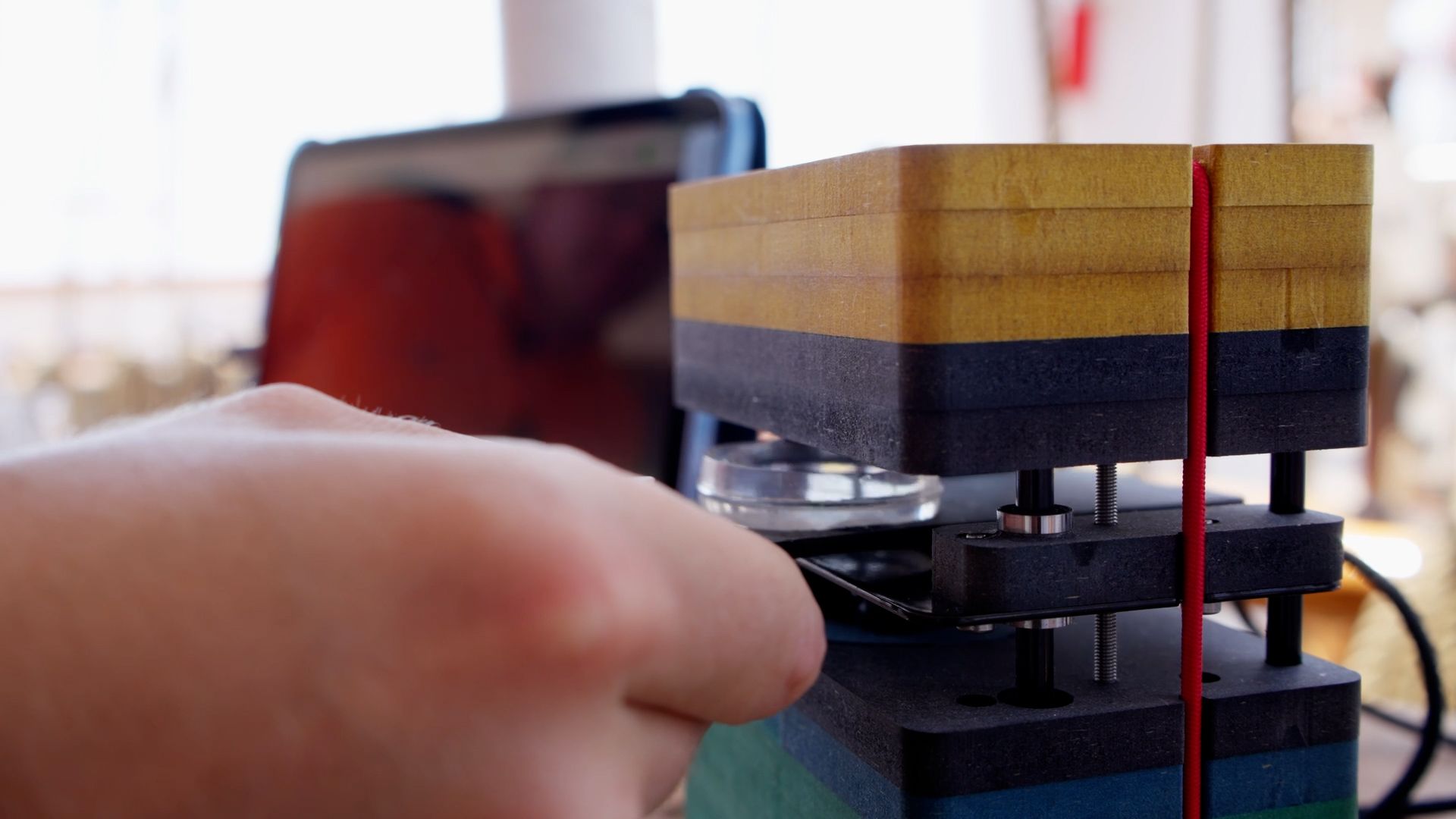

Emmanuel works together with Lucie Cassarino, Science coordinator for the One Ocean Expedition to take samples of the ocean, at the same time that the satellites high above Statsraad Lehmkuhl take their pictures. Lucie launches what she call "the High speed net". It looks similar to the Bongo net, but with a much smaller opening.

The Bongo net is used when the ship is lying still, the High speed net is dragged along with the ship, like the Manta net.

– The net is specially designed to capture microorganisms as the ship moves, Lucie explains. First we collect a sample with the net, and then we filter it. We do this to collect eDNA, that is environmental DNA.

A biological fingerprint

Environmental DNA sampling is a technique that tells the scientists which organisms that are present in the sea by analyzing the traces of genetic material they leave behind in the water. This means they can discover a wide range of marine life, even those that are too small to see or that might escape traditional nets.

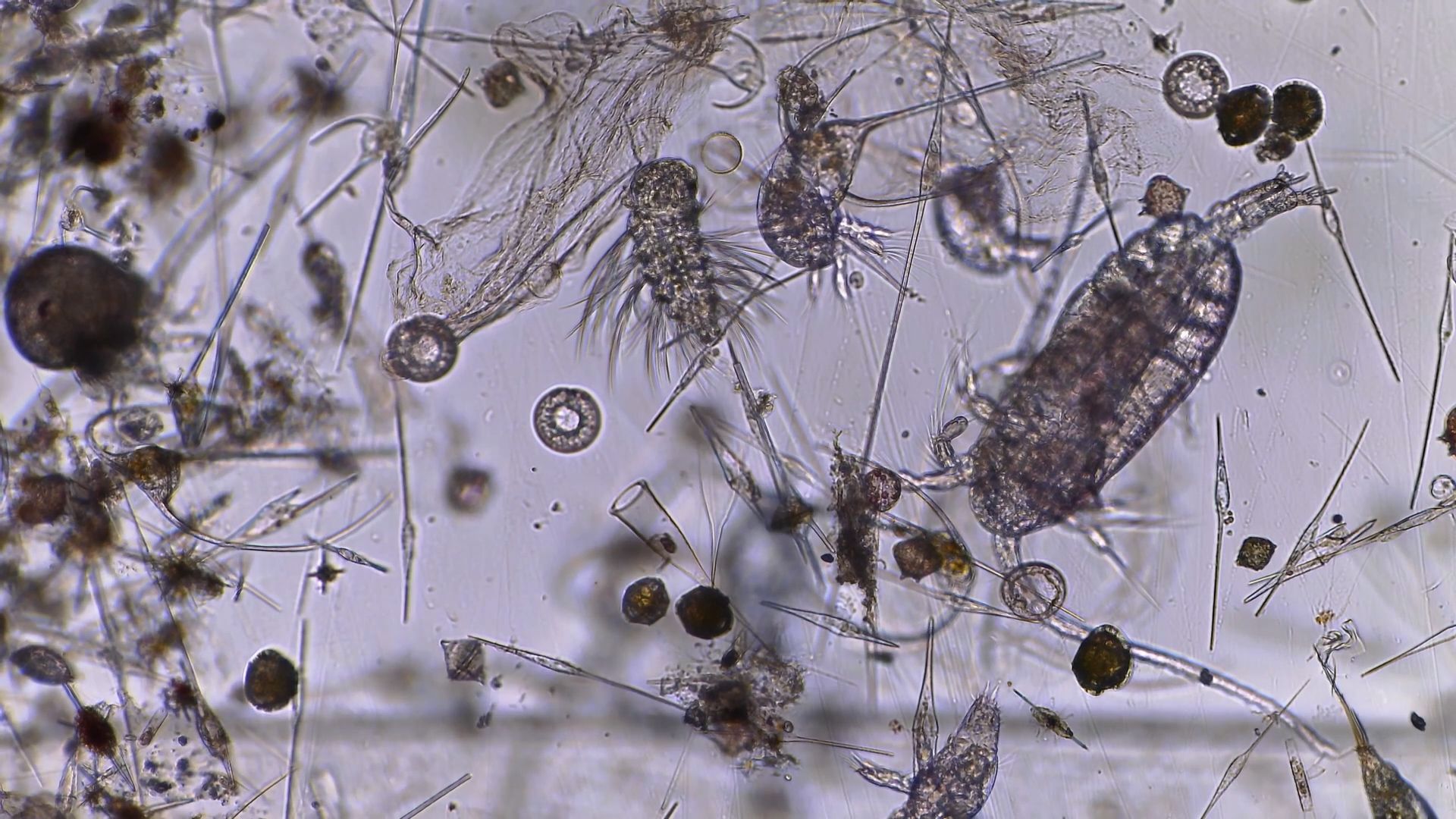

A microscope is also used.

– We use the microscope to take pictures of the organism we can see in the sample, Lucie says. Then we compare these different measurements to make sure that we do not make mistakes, that we identify the correct species.

The combination of eDNA and microscopy offers a powerful way to verify what's truly in the water, from phytoplankton and zooplankton to countless unknown microorganisms.

– We hope to find everything that you have in the ocean. Even very, very, very small microorganisms, says Lucie.

Not complete

The scientists look up what they have found in a library of known DNA samples.

– Go and find all the match-ups in that library and say, oh, this was there, this was there, this was there, this was there, and so on, says Emmanuel.

But the library is not complete. This is why sequencing of the collected DNA is so important.

– We get sequences of all the organisms that are in the sample, but you see, most of them we don't know, says Emmanuel.

Piece by piece

So - despite the enormous potential of satellite and eDNA synergy, the field still faces major limitations.

– It is a problem that we're still very data poor in many ways, Emmanuel emphasizes. And until we get a much more comprehensive view of the ocean, it's really, really hard to interpret the observations we have.

This is how science works, adding small pieces of information, one after another - making the overall view better and better. In this case, make it possible to calibrate and improve satellite data so that it can reflect what is really happening in the ocean, without needing to physically be there.

– The data we are collecting here are going to be put in the database of the satellite. So it can recognize what's in the ocean right from the atmosphere, says Lucie.