Long, narrow, and equipped with fins like the fish it’s named after, the Manta Trawl is used to reveal how much microplastic is floating in the sea.

It’s easy to forget when watching sailors haul ropes, climb masts, and scrub decks, but Statsraad Lehmkuhl is in fact a modern research vessel - disguised as a tall ship.

Beneath the bow lies a custom-built underwater pod, nicknamed “the Fish,” housing a scientific echosounder, hydrophones, and other marine research instruments. A weather station is mounted high in the rigging, and from the deck, scientists deploy equipment to measure and sample the ocean far beneath the keel.

Among their tools are several fine-mesh nets used to collect and study plankton and other small organisms drifting in the ocean.

Like a ray

One of these tools is called the Manta Trawl. The net got its name because it resembles a manta ray and mimics the ray’s feeding method of filtering water. But this net captures more than just food.

– The manta ray feeds on plankton and small creatures. The issue is that microplastics have a similar size. There's a high likelihood that they also feed on microplastics, explains Lena Schaffeld, a master’s student at Instituto do Mar (IMAR) at the University of the Azores in Portugal.

Long and narrow

The Manta Trawl is deployed with a small crane, and Lena adjusts the lines in rhythm with the ship’s movement.

– Really calm conditions today. So the manta is flowing.

The trawl itself is long and narrow, with two fins extending outward from the rectangular mouth. At the end is a filter that collects everything the net scoops up as it’s towed through the surface water.

One of the features that makes the One Ocean Expedition unique is that Statsraad Lehmkuhl gathers scientific data continuously along its route. This makes it possible to observe how ocean conditions change from place to place.

White little dots

On May 12, while sailing between Ireland and France, the net collected mostly zooplankton. But by May 19, when the ship reached the Portuguese coast, the result was dramatically different.

– This here is our sample that we collected between Ireland and France. And we can see a lot of zooplankton, while on the other hand, this is the sample we collected a week later once the expedition reached the Portuguese coast. Oh, wow. Look at this. All the white little dots. It's plastic fragments, Lena says, holding up the two samples.

Below you can see the difference, the first two images are from between Ireland and France, the rest are taken outside Portugal. All photos: Matteo Baratella

Tracking the particles

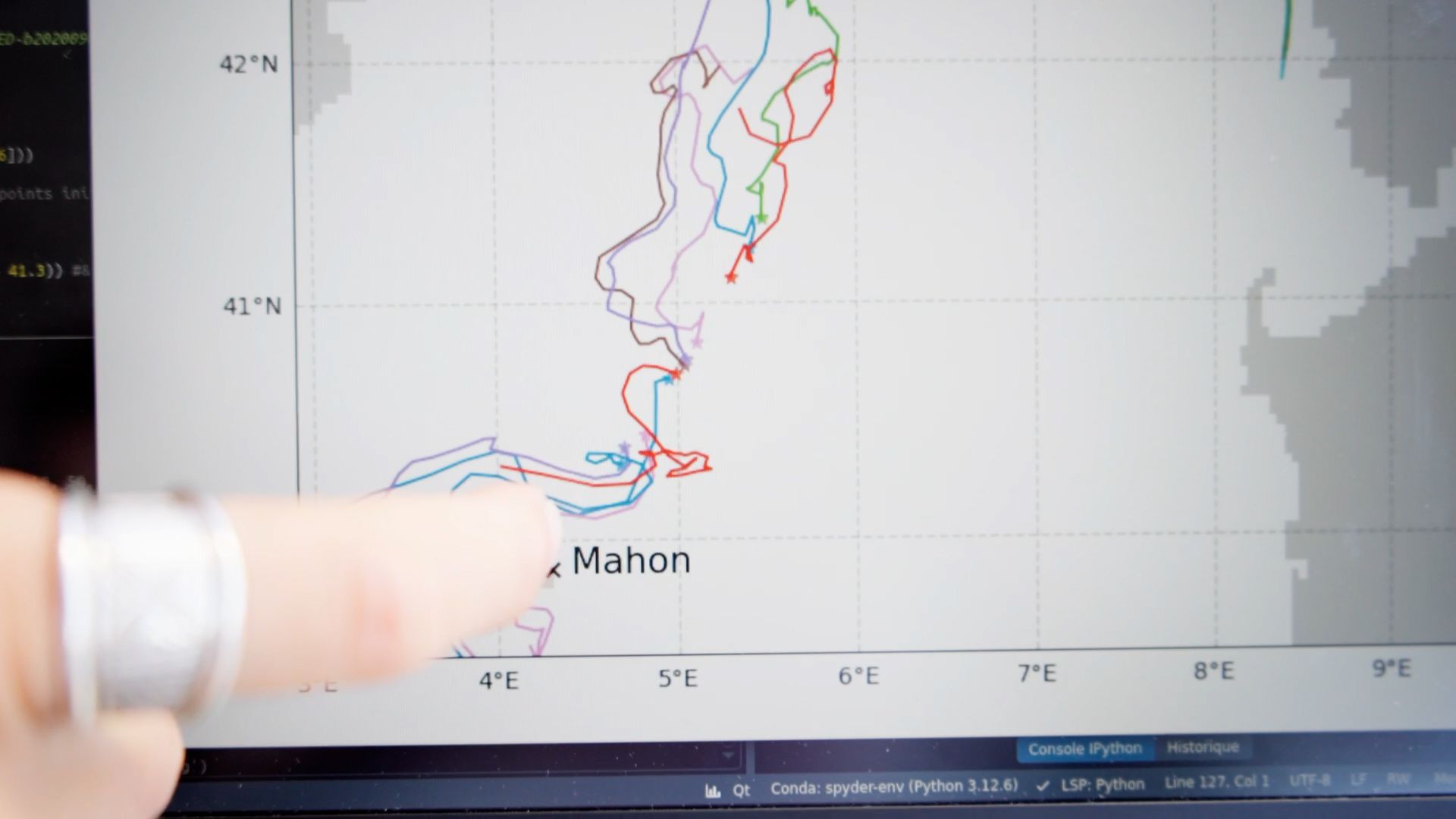

Researchers use various tools to count particles and analyze the water samples. These data are then combined with numerical models that simulate ocean currents, allowing scientists to trace particles back to their likely sources.

– By collecting microplastics with a multi-tool, we can count the particles we find in the sample. And then, using numerical modeling, we can simulate the ocean currents and follow the particles along the route and identify their potential sources, says Charlotte Cunci, a PhD candidate at the Mediterranean Institute of Oceanology at the University of Toulon in France.

One of the main goals of the project is to determine where plastics accumulate and how they travel across the ocean.

– With that information, we can change the regulation of plastics and reinforce it to protect marine areas, Charlotte adds.

A strong impression

This is not the first time the researchers have found plastic in the sea, but the sheer volume of microplastics in every single sample leaves a strong impression.

– For me, it's exciting to do all of this sampling, but generally I'm quite sad when I see so much plastic. We have a lot of plastic in the ocean, and when we can show that, it gives us leverage to push the ocean laws and do something about it, says Lena.

– I think if we mess it up, we also have to fix this, so I'm very glad to be on this voyage. Communicate and share the knowledge to raise awareness, she concludes.

Not as scary as they look

Manta rays may look intimidating - flat-bodied, winglike fins stretching out to the sides, a long narrow tail, and two horn-like lobes flanking the mouth. The largest can weigh over 1,000 kilos and have a “wingspan” of six to seven meters.

But looks can be deceiving. Their mouths are large, but their teeth are tiny.

When feeding, they open their mouths wide and glide through the water, filtering out shrimp, krill, crabs, and other crustaceans. When plankton is especially dense, the gills can clog, forcing the ray to “cough” to clear the flow of water and oxygen. At such moments, a cloud of plankton may billow around the ray - an irresistible feast for the cleaner fish that often swim alongside.